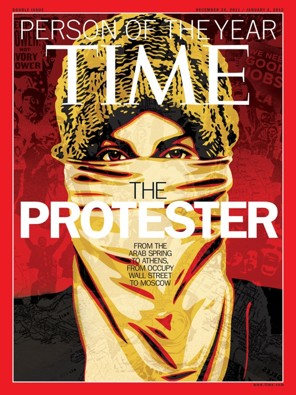

Dissident Prof notes Time Magazine's celebration of the Protestor by its designation of the Protestor as the Person of the Year. Some Protestors, however, are more equal than others and the U.S. media turned its gaze on the Protestor from one of the most pampered and flattered groups in history: the American college student, who ostensibly were inspired by protests in the Middle East. The equally self-flattering media, however, little noted the assault on Poland by the communist leftovers. Ewa Thompson, Professor of Slavic Studies, here brings us up to date on the alarming developments.

Dissident Prof notes Time Magazine's celebration of the Protestor by its designation of the Protestor as the Person of the Year. Some Protestors, however, are more equal than others and the U.S. media turned its gaze on the Protestor from one of the most pampered and flattered groups in history: the American college student, who ostensibly were inspired by protests in the Middle East. The equally self-flattering media, however, little noted the assault on Poland by the communist leftovers. Ewa Thompson, Professor of Slavic Studies, here brings us up to date on the alarming developments.

Something is Rotten in the Kingdom of Poland, by Ewa Thompson

We have forgotten about non-Germanic Central Europe. Sovereign debt, unemployment, and Middle East instability command America’s attention. In 1989, postcommunist Central Europe received a good-bye kiss and was sent off with best wishes of good luck. The Soviet army was gone and countries between Germany and Russia regained sovereignty. Some Western politicians and do-gooders urged the former captive nations to forgive and forget the crimes of those who once collaborated with the Soviets. It was bad advice. In Poland and elsewhere, former collaborators put on the mantle of social democrats and continued to participate in political life. It was assumed that such universal forgiveness with regard to communist crimes would solve all problems. Twenty years later there is evidence that this has not happened.

We have forgotten about non-Germanic Central Europe. Sovereign debt, unemployment, and Middle East instability command America’s attention. In 1989, postcommunist Central Europe received a good-bye kiss and was sent off with best wishes of good luck. The Soviet army was gone and countries between Germany and Russia regained sovereignty. Some Western politicians and do-gooders urged the former captive nations to forgive and forget the crimes of those who once collaborated with the Soviets. It was bad advice. In Poland and elsewhere, former collaborators put on the mantle of social democrats and continued to participate in political life. It was assumed that such universal forgiveness with regard to communist crimes would solve all problems. Twenty years later there is evidence that this has not happened.

There was no accounting in Poland for martial law introduced by the Soviet-imposed General Jaruzelski in 1981. There was no accounting for the mysterious beatings to death of several Roman Catholic priests who supported Solidarity, and countless others who died in conditions of hardship created by martial law. Members of the secret police who participated in the suppression of Solidarity are now living in comfortable retirement, often receiving pensions several times higher than the pensions of those whom they once terrorized. The famous “bottom line” (Tadeusz Mazowiecki’s expression) that was supposed to separate the communist past from the free present turned out to be a mantle concealing the urge to commandeer society that the communist ideologues once advocated and practiced.

On December 13, 2011, a 10,000-strong demonstration marched in the streets of Warsaw demanding investigation of the mysterious 2010 crash of the Polish President’s plane over the Russian city of Smolensk. The present Polish government washed its hands of the catastrophe and allowed the Russians to “investigate” what happened. The Russians destroyed the plane—they literally chopped it to pieces—and announced that the catastrophe was the fault of the Polish pilots.

On December 13, 2011, a 10,000-strong demonstration marched in the streets of Warsaw demanding investigation of the mysterious 2010 crash of the Polish President’s plane over the Russian city of Smolensk. The present Polish government washed its hands of the catastrophe and allowed the Russians to “investigate” what happened. The Russians destroyed the plane—they literally chopped it to pieces—and announced that the catastrophe was the fault of the Polish pilots.

Similar demonstrations took place in other cities. On November 11, 2010, Polish Independence Day, an even larger demonstration marched through the streets of Warsaw waving Polish national flags and singing patriotic songs. This demonstration was met by, among others, a crowd of German (yes!) leftists who apparently came to Poland on that day to prevent “Polish nationalists” from demonstrating on Polish Independence Day.

In 2005–7, the late President Lech Kaczynski’s attempt at vetting the former communist officials was met with fury and ridicule by, among others, the country’s most influential newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza and its ideological guru Adam Michnik. Soon afterwards, a leading editor of Gazeta Wyborcza, Leslaw Maleszka, was exposed as a former communist agent implicated in the death of one of his personal friends. Michnik’s ability to place his anti-vetting article in the New York Times helped destroy President Kaczynski’s reputation in international circles. Michnik alleged that the Kaczynski government was engaged in a witch hunt. Regrettably, many former supporters of Solidarity fell in for this misrepresentation. The vetting was scrapped. In 2007, the anti-vetting party Civic Platform won a majority in the parliament.

The presence of former communists in the Polish privileged class is one reason why the man in the street is bitter. The Smolensk tragedy is another. In 2010, President Kaczynski and 95 accompanying members of the country’s elite perished in a plane crash near the Russian city of Smolensk. In unseemly haste, Speaker of the Sejm (now President), Bronislaw Komorowski, took over the offices and documents of the late President Kaczynski. Komorowski’s alleged ties to the communist secret services (directed from Moscow) did not help to build trust in his presidency.

When the Civic Platform won for the second time in 2010, vetting à rebours began. Members of the opposition party were systematically weeded out of public television and other public media. Coincidentally, the majority stake in the most respected Polish daily, Rzeczpospolita, was purchased by Grzegorz Hajdarowicz, a businessman who seems to believe in capitalism but does not understand that capitalism does not automatically deliver a free society.

In December 2011, a minor leftist politician Tomasz Kalita tweeted that today’s opposition party, Law and Justice, is very much like the Solidarity movement of yore. This was eagerly picked up by Law and Justice supporters. However, this plus $5 will only buy you a cup of coffee at Starbucks. In other words, an apt comparison does not change the political and financial situation. In a country where the major media depend upon government support and where capital is lacking, no access to public television means marginalization.

Little by little, Polish citizens begin to declare that they have been cheated by their government. That the Civic Platform is neither civic (it represents oligarchy interests) nor a platform (it is a place from which orders are given rather than a forum where issues are discussed.) The last drop was the Tusk government’s apparent readiness to share Poland’s meager foreign reserves with the IMF in order to bail out the heavily indebted euro countries. It is worth noting that neither President Vaclav Klaus of the Czech Republic nor President Victor Orban of Hungary showed similar inclinations. Poland is not even in the eurozone, and its GDP per capita is several times smaller than that of Italy: why should its poor citizens tighten their belts even more to accommodate the richer nations? Economist Krzysztof Rybinski points out that according to EU rules, central banks are forbidden to finance the governments of any country. Banks are supposed to be independent. Poland is the eighth most indebted country in the world, and its tiny foreign reserves are now supposed to be used, in part, to bail our its richer colleagues in the EU. That makes no sense!

The opposition internet sites state that Poles have been turned from citizens into viewers. Recent developments in their country should be noted by the American media, if only because volatility in non-Germanic Central Europe has the potential of precipitating an all-European heart attack. Poles are mild people, and the scenes from Cairo or Tripoli will not be duplicated in Warsaw. Maybe because no body bags are likely to be coming out of Central Europe in the foreseeable future the Western press ignores this part of the world and its key state, Poland. There is no oil there either. But—two world wars started in Central Europe, and the feeling of nationhood is strong among Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, Serbs, Croats, Latvians, Lithuanians, Estonians. They will not yield to forces that want to homogenize them into flavorless subjects of other nations’ interests, under the pretext that they are being remade into “citizens of the world.”

The opposition internet sites state that Poles have been turned from citizens into viewers. Recent developments in their country should be noted by the American media, if only because volatility in non-Germanic Central Europe has the potential of precipitating an all-European heart attack. Poles are mild people, and the scenes from Cairo or Tripoli will not be duplicated in Warsaw. Maybe because no body bags are likely to be coming out of Central Europe in the foreseeable future the Western press ignores this part of the world and its key state, Poland. There is no oil there either. But—two world wars started in Central Europe, and the feeling of nationhood is strong among Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, Serbs, Croats, Latvians, Lithuanians, Estonians. They will not yield to forces that want to homogenize them into flavorless subjects of other nations’ interests, under the pretext that they are being remade into “citizens of the world.”

Ewa Thompson is Research Professor of Slavic Studies and former Chairperson of the Department of German and Slavic Studies at Rice University. She has taught at Rice, Indiana, Vanderbilt, and the University of Virginia, and has lectured at Princeton, Witwatersrand (South Africa), Toronto (Canada), and Bremen (Germany). She received her undergraduate degree from the University of Warsaw and her doctorate from Vanderbilt University. She is the author of five books (one of them edited and coauthored), about fifty scholarly articles, and hundreds of other articles and reviews. Her book Imperial Knowledge: Russian Literature and Colonialism (2000) has been translated into Polish, Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Chinese. She has published scholarly articles in Slavic Review, Slavic and East European Journal, Modern Age, and other periodicals and has done consulting work for the National Endowment for the Humanities, U.S. Department of Education, and other institutions and foundations. She is Editor of Sarmatian Review, an academic quarterly on non-Germanic Central Europe. Her area of specialization is Central and Eastern Europe.

Ewa Thompson is Research Professor of Slavic Studies and former Chairperson of the Department of German and Slavic Studies at Rice University. She has taught at Rice, Indiana, Vanderbilt, and the University of Virginia, and has lectured at Princeton, Witwatersrand (South Africa), Toronto (Canada), and Bremen (Germany). She received her undergraduate degree from the University of Warsaw and her doctorate from Vanderbilt University. She is the author of five books (one of them edited and coauthored), about fifty scholarly articles, and hundreds of other articles and reviews. Her book Imperial Knowledge: Russian Literature and Colonialism (2000) has been translated into Polish, Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Chinese. She has published scholarly articles in Slavic Review, Slavic and East European Journal, Modern Age, and other periodicals and has done consulting work for the National Endowment for the Humanities, U.S. Department of Education, and other institutions and foundations. She is Editor of Sarmatian Review, an academic quarterly on non-Germanic Central Europe. Her area of specialization is Central and Eastern Europe.