“Let her and Falsehood grapple; whoever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?” John Milton Areopagitica

“Let her and Falsehood grapple; whoever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?” John Milton Areopagitica

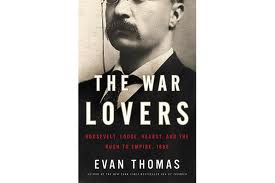

The War Lovers: A Critical Review by Brian E. Birdnow, Posted August 8, 2012

In The War Lovers (Little Brown, 2010), Evan Thomas, of Newsweek, the troubled bastion of mainstream liberal journalism, tries his hand at popular history and produces a sprightly, readable and well-written volume. Most members of the historical profession resent the journalists poaching on our game preserve. As a historian, I, however, welcome outsiders into the game and believe that new perspectives can be helpful and that journalists who write well often improve on the ponderous, pedantic, and pretentious pronouncements of the academic historians. So the historians need to hold their water when the so-called amateurs invade their field…provided that the history the amateurs write is good and credible. Unfortunately, in the case of Evan Thomas and The War Lovers, this is not true.

Evan Thomas’s thesis is fairly simple and straightforward. He argues that openly aggressive and even militaristic American VIPs wanted war with someone by 1898, and that Spain presented an acceptable target. Who were these “jingoes,” to use the popular phrase of the time? Thomas names Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt on the political side of things and “The Chief,” William Randolph Hearst, on the media side, as mass circulation newspapers became increasingly influential in American life. He further claims that ordinarily sober people like Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and John Hay caught the war fever, and that indecisive folks like President William McKinley swam along with the tide. Principled Americans who opposed the “Rush to War,” like House Speaker Thomas B. Reed, and the renowned philosopher William James were overwhelmed, and in the case of Reed, they were ruined by the war fever, and the patriotic surge following the easy victory in the conflict.

Mr. Thomas tips his hand when he compares the Spanish-American War to another so-called “War of Choice,” that being, of course the Iraq War of 2003. According to Thomas, “It [The Spanish-American War] has some eerie parallels to the invasion of Iraq, another war of choice not immediately vital to the national security, but ostensibly waged for broader and shifting humanitarian reasons.” He also states that the period following the 9/11 attacks resembled the winter and spring of 1898 in the sense that war fever gripped the country. The emotional pull proved to be strong enough not only to beguile the uninitiated rubes, who always fall for such buncombe, but even to fool the deep thinking sophisticates among the fourth estate, people like Evan Thomas, as he himself ruefully notes. In a way Thomas is using the book as a therapeutic exercise, one that he hopes will help make sense of his lapse in judgment during 2001-2003.

Mr. Thomas tips his hand when he compares the Spanish-American War to another so-called “War of Choice,” that being, of course the Iraq War of 2003. According to Thomas, “It [The Spanish-American War] has some eerie parallels to the invasion of Iraq, another war of choice not immediately vital to the national security, but ostensibly waged for broader and shifting humanitarian reasons.” He also states that the period following the 9/11 attacks resembled the winter and spring of 1898 in the sense that war fever gripped the country. The emotional pull proved to be strong enough not only to beguile the uninitiated rubes, who always fall for such buncombe, but even to fool the deep thinking sophisticates among the fourth estate, people like Evan Thomas, as he himself ruefully notes. In a way Thomas is using the book as a therapeutic exercise, one that he hopes will help make sense of his lapse in judgment during 2001-2003.

The book often dwells in the land of myths and half-truths, rather than facts. Thomas eagerly relates stories of dastardly American behavior, and excuses examples of such deeds directed at the USA, and individual Americans. For example, on page 120, Thomas writes, “In 1891 President Harrison had threatened to send the navy to punish Chile for a minor imbroglio involving some drunken American sailors after a bar brawl in Valparaiso.” The reality of the situation was much more grim. A Chilean mob had attacked a party of American sailors who were on liberty during a port visit. Two sailors had been killed and another eighteen had been badly beaten. Harrison asked for naval action against Chile after the Chilean government brushed off diplomatic efforts. Still, this is not mentioned because it doesn’t fit the overall narrative and thesis of needless American muscle flexing in the 1880s and 90s.

Thomas is at his most inaccurate when discussing the fighting in the Philippines during the Spanish War and its aftermath. He argues, naturally, that the American attack on the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, proves that the war was an imperialist venture (He does not mention that the American commercial class generally opposed the war) and that we intended to keep the Philippine archipelago after the war, for the purpose of building an American empire. He is wrong on both counts. First of all, Assistant Naval Secretary Theodore Roosevelt (he joined the army later) was following the classic military dictum of striking your enemy wherever you find him when he ordered the U.S. Asiatic squadron to attack the Spanish positions guarding Manila Bay in the event of war. Likewise, it is disingenuous to suggest that American forces could or should have retired from Manila following the armistice of August 12, 1898. A strong German fleet carrying ground forces stood by just outside of Philippine coastal waters, with orders from Berlin to seize the islands, and declare them a German colony if the Americans departed. Leaving the Philippines at this point would have been tantamount to presenting the Germans with a gift-wrapped present after the successful American effort to dislodge and eject the ruling Spaniards. This was not a viable option and a good historian knows these facts.

The author returns to his practice of blaming Americans for not playing fair, while disregarding the sins of our foes when discussing the Philippine insurrection, as well. He notes that the nasty war of 1899-1902 saw “…atrocities on both sides.” He does, however, list four specific types of American brutalities but does not note the common Filipino practice of wrapping American prisoners in chains and drowning them in cauldrons of boiling water. He also overlooks the Filipino rebels feeding captured Americans to sharks in Lingayen Gulf, and turning prisoners over to the tender mercies of headhunters in the remote jungles. Thomas is more interested in telling his readers, in rather breathless tones, that the U.S. forces borrowed a Spanish torture method and used it for the first time in 1899. It is commonly known as “waterboarding.”

The author returns to his practice of blaming Americans for not playing fair, while disregarding the sins of our foes when discussing the Philippine insurrection, as well. He notes that the nasty war of 1899-1902 saw “…atrocities on both sides.” He does, however, list four specific types of American brutalities but does not note the common Filipino practice of wrapping American prisoners in chains and drowning them in cauldrons of boiling water. He also overlooks the Filipino rebels feeding captured Americans to sharks in Lingayen Gulf, and turning prisoners over to the tender mercies of headhunters in the remote jungles. Thomas is more interested in telling his readers, in rather breathless tones, that the U.S. forces borrowed a Spanish torture method and used it for the first time in 1899. It is commonly known as “waterboarding.”

In the final chapter of the book Thomas takes dead aim at the nascent American Empire. He argues, of course, that we kept the Philippines to use as a springboard for vaulting into China. He accepts this as a given, even though Secretary of state John Hay (who Thomas dismisses as being a thinker of little imagination, and no vision) defended Chinese territorial integrity in 1899 and made the maintenance of Chinese independence the cornerstone of American foreign policy in East Asia for the next thirty years. This policy of guaranteeing Chinese independence was bound to cause complications with Russia and Japan, but we pursued it nonetheless.

In The War Lovers, Evan Thomas writes a book that serves as a good evening or weekend read. It is, however, not a reliable history of its time.

Brian Birdnow, a frequent contributor, teaches history at Lindenwood University and at Harris Stowe University, both in Missouri.

Do you know of a bad book? Send Dissident Prof a critique and help readers and students!